The Muslim and Jewish roots of Spain

If you've read anything about the history of Andalucia (and Spain), you'll know that its cultural legacy is rich and varied: the Moors ruled what they called "Al-Andalus" until the 12th century, with the final stronghold being captured in 1492. Many stayed on after the Catholic Kings expelled them, becoming moriscos - Moorish converts to Christianity.

These were the craftsmen who built many of the monuments we still see today, such as Seville's magnificent Alcazar, in the mudejar style. Granada is one of the cities in Andalucia which most retains a Moorish feel, thanks to the Alhambra and Albaicin barrio, with its narrow, windy streets and many traditional Moorish carmenes, houses with walled gardens. In addition, Cordoba and Seville are both well-known for their juderias, Jewish quarters. Seville's was in what is now barrio Santa Cruz; the cross in Plaza Santa Cruz, next to the Murillo Gardens, commemorates the former site of one of the area's many synagogues in centuries past.

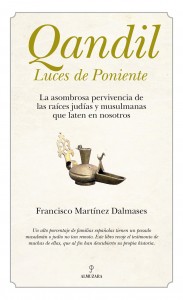

Indeed, young Jews chose Seville to celebrate their Purim festival last month. Spanish Jews were known as Sefardi. So I was fascinated to read about a new book which looks at this subject. Called Qandil: Luces de Poniente (Light of the West), and written by Francisco Martinez Dalmases, it is subtitled "the astonishing survival of Jewish and Muslim roots in the Spanish". The book tells the stories of various families who have rediscovered their multiracial roots, in the not-so-distant past. It states that a "high percentage" of families have ancestors of these two faiths.

You can tell this just by looking at the many dark eyed, dark-haired Andalucians, though not all will thank you for pointing it out to them. Many Spanish don't want to be associated with their Moorish forebears. It's not generally something they are proud of. Over the last few years in Britain, and for much longer in the US, there's been a trend for tracing your family history, with TV series showing tearful actors and other celebrities finding out their granddad was in prison, or that there's another whole branch of the family they didn't know about.

I can't see it catching on here in Spain; there may be some who would welcome knowledge about their ancestry, but I reckon they're in the minority. The book reconstructs Spanish families' pasts, and helps them to discover their own history - many have ancestors who had to hide - or ignore - their culture and roots. "You only have to scratch the past a bit to find out who we really are," says the author.From the rich oral tradition to the old tales of silent people (who couldn't practise their religion openly for fear of persecution from the Catholic authorities), from research by forgotten historians to the spiritual traces in Spanish people, we get a story never previously told. The testimony of those who, hidden among us, descendants of Jews and Muslims, have remained in denial until today. Who Do You Think You Are? al español - I can't see it catching on as Big Brother and Pop Idol did. But I'll be buying this book, and I hope many other people do too.